At an annual women’s rights convention in Illinois, several new rules were laid down for members. Attendance was limited to 100 people, the general public were barred from participating and chairs at the meeting were set four feet apart.

It could almost be a scene from 2020, the kind of thing societies around the world are implementing as they begin to cautiously emerge out of coronavirus lockdown measures and adjust to a new, socially distanced way of life.

But this meeting took place in late October 1918, against the backdrop of the so-called “Spanish flu” pandemic, one of the deadliest in history, thought to have killed 50 million people worldwide by the time it ended. And the women taking part were members of the Illinois Equal Suffrage convention, eager to follow public health guidelines as well as to continue the campaign for the American woman’s right to vote.

This August will mark the centennial of the 19th Amendment, and thus 100 years of women’s suffrage across the United States. As the plans to celebrate the anniversary have been upended by COVID-19, historians are looking back to the determination of the suffragists in the face of a similarly challenging moment. “The suffragists have shown us how to persevere through the highs and the lows,” says Anna Laymon, executive director of the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission. “It’s easy to find inspiration in their stories and their work. There’s a refrain of ‘if the suffragists can do what they did, we can get through this.’”

The 1918 flu outbreak started in the spring of 1918 and, in the U.S., was first identified in military personnel. The lack of advanced medicine and a vaccine meant that, much as is the case today, governments encouraged non-medical interventions such as quarantines, mask-wearing and good personal hygiene. Meanwhile, several countries around the world had already passed legislation for the enfranchisement of women. By the time the flu outbreak was first identified in the U.S. in the spring of that year, the momentum for American women’s suffrage was building rapidly. A patchwork of legislation in different states enabled women to vote in some local elections, but Congress had not yet ratified the 19th Amendment.

“This is also a moment when women are doing a lot of visible protests modeled after British suffragists,” says historian Allison K. Lange, associate professor of history at Wentworth Institute of Technology and a consulting historian for the Commission. Legislation passed in 1918 gave some women in the U.K. the right to vote, subject to specific criteria, and transatlantic tactics were shared. American women were organizing parades and the National Women’s Party started picketing outside the White House in January 1917, the same month that the U.S. entered World War I. Four months later, in April 1917, Jeannette Rankin of Montana was elected to the House of Representatives as the first female member of Congress.

But American women campaigning for the right to vote found themselves engaged in three different battles — against the practical problems and the tragedies that the flu wrought, against the crisis of the then-ongoing World War I, and against those opposed to women’s suffrage. “Everything conspires against women’s suffrage,” one local suffragist told the New Orleans Times-Picayune in October 1918.

That sentiment resonates today for Lange, author of the forthcoming Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. “That was my takeaway quote from the newspaper articles, because I think we all kind of feel that way, whether it’s about the 1918 flu or the suffrage centennial actually happening,” she says.

Lange came across that particular article reported from New Orleans while researching how the suffrage movement responded to the 1918 flu, a topic that has often been overlooked in historical literature, which has tended to focus more on the impact of the war on the suffrage movement. As the fight for the vote was peaking, tens of thousands of women entered roles in the Women’s Land Army to fill the jobs that men had left when they went to war, and eight million women volunteered as American Red Cross workers taking on duties from nursing to mechanics and motorcycle messengers. “In some ways, women’s World War I contribution and the flu crisis, at least especially initially, overlapped,” says Lange.

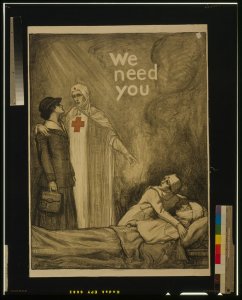

Poster showing a Red Cross nurse appealing to a young woman for help, as another nurse tends to a wounded man; created by Albert Sterner 1918.

Library of Congress

The simultaneous challenges of the war and the pandemic forced the suffragists to adapt their priorities and campaigning methods, particularly in the face of the influenza, which prevented the public demonstrations and events that they had been so well known for. More radical suffragists felt their efforts had been thwarted, but moderate campaigners saw these obstacles as opportunities to show their patriotism and contribution to the national effort.

Although they wouldn’t have labelled their actions as “social distancing” at the time, suffragists aligned themselves with the message of the health authorities. They postponed campaigns, wore masks and focused on petitions instead of large-scale public events. Local women’s organizations signed up to volunteer with the Red Cross and a key part of their work was to help discharged soldiers recover from the flu, as several outbreaks were at military camps. It was also a moment of possibility for a more diverse group of women: during the pandemic, 18 black nurses were admitted to the Army Nurse Corps and American Red Cross, which had only previously admitted and deployed white nurses.

Between the war effort and the flu response, more moderate suffragists endeavored to show a kind of “model citizenship,” says Lange. “While the public spectacles were extremely valuable in keeping the issue in the news and in people’s minds, the rhetoric of the more moderate suffragists was adopted by public officials.” And that rhetoric helped further the argument that women’s suffrage was socially acceptable, even to those who might not otherwise have supported it.

That patience paid off, as President Woodrow Wilson addressed the Senate in support of women’s suffrage in September 1918. “This war could not have been fought…if it had not been for the services of the women—services rendered in every sphere,” he said, having written a telegram to the Illinois suffragist group just four days later to praise the way “women’s work for suffrage was being carried out during the war.”

While the suffragists themselves recognized the ways the flu impacted their work, their contribution to fighting the pandemic was perhaps overlooked, even at the time, in comparison to their contribution to the war effort. “It was assumed that women would do this [nursing] work and risk their lives to be caregivers,” says Lange. Just a week later, the influenza pandemic would claim victims in Washington, D.C., and Congress itself, showing just how much it infiltrated all aspects of life.

Despite the pandemic, the suffrage movement continued campaigning with determination and on June 4, 1919, the 19th Amendment, granting U.S. women the right to vote, was passed by Congress and sent to the states for ratification.

For Lange, the suffragists’ ability to adapt and change in the face of steep obstacles is a timely reminder. “They were constantly adapting new ideas and new ways of thinking about the world, and that’s exactly the kind of thing we’re hoping to do right now,” she says. “I hope we take away the idea of persistent perseverance, and hopefully see new opportunities in that adaptation.”

No comments:

Post a Comment