Published: Jan 27, 2014

By

John Gever, Deputy Managing Editor, MedPage Today

Reviewed by

Zalman S. Agus, MD; Emeritus Professor, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Exposure to the notorious pesticide DDT may play a role in development of Alzheimer's disease, a small case-control study suggested.

Levels of dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), the main metabolite of DDT, averaged 2.64 ng/mg in serum (SE 0.35) in 86 individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, compared with 0.69 ng/mg (SE 0.1) in 79 controls (P<0 .001="" a="" according="" href="http://eohsi.rutgers.edu/content/directory?profile=84" nbsp="" style="color: #008be8; outline-style: none; text-decoration: none;" target="_blank" to="">Jason R. Richardson, PhD

, of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, N.J., and colleagues.

Looked at another way, those study participants in the highest tertile of serum DDE level had quadruple the risk of carrying an Alzheimer's disease diagnosis (odds ratio 4.18, 95% CI 2.54-5.82 versus the lowest tertile), the researchers reported online in

JAMA Neurology.

Mean scores on the 30-point Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) were lower by 1.605 points (95% CI 0.114-3.095) in the highest versus lower tertiles of serum DDE, Richardson and colleagues also found.

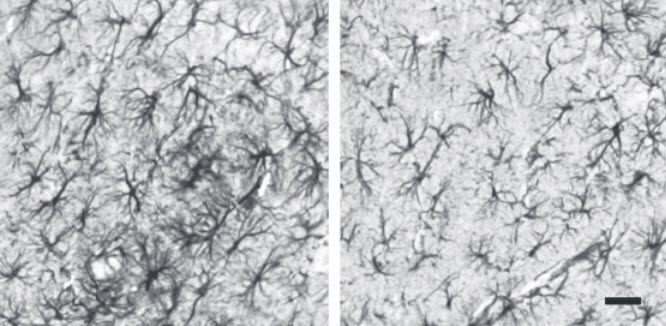

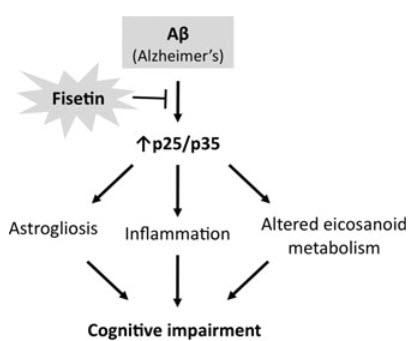

And, they identified a potential mechanism whereby DDT/DDE exposure may promote development of Alzheimer's disease. In vitro experiments with human neuroblastoma cells showed that exposure to either chemical boosted secretion of amyloid precursor protein -- the parent of beta-amyloid protein. Beta-amyloid plaques in the brain are a major hallmark of Alzheimer's disease.

Although DDT was banned in the U.S. in 1972, Richardson and colleagues noted, it is still in use elsewhere in the world. Americans may continue to be exposed to the pesticide through imported foods. Moreover, it is very long-lived in the environment, and exposure to contaminated soils may be another route of continuing exposure.

The researchers cited findings from recent federal surveys that found 75% to 80% of participants had measurable levels of DDE in serum.

Other researchers not involved in the study cautioned that it was small, preliminary, and not designed to establish causality.

Huntington Potter, PhD, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora, told

MedPage Today that it was essentially "a pilot study."

But Potter, as well as authors of an accompanying editorial in JAMA Neurology, noted that it was important for suggesting a specific environmental factor that may contribute to Alzheimer's disease risk -- something that has long been hypothesized but with few specific clues for where to look.

"Richardson and colleagues have provided both a wake-up call to explore environmental influences and pointed us to a first area to assess -- pesticides, which have already been implicated in other human illnesses," wrote

Steven DeKosky, MD, of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, and

Sam Gandy, MD, PhD, of the Mount Sinai Alzheimer's Disease Research Center in New York City, in the editorial.

For the study, Richardson and colleagues recruited two cohorts of participants, one at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and the other at Emory University in Atlanta, from 2002 to 2008. Blood samples were drawn and the investigators decided by consensus, on the basis of

published diagnostic criteria, whether participants had Alzheimer's disease or were cognitive normal.

One finding that tended to reinforce the connection between DDE levels and Alzheimer's disease risk was that participants with high levels and the APOE4 genotype -- well known to dramatically increase the risk of Alzheimer's disease risk -- showed an exaggerated decrease in MMSE scores relative to those with low DDE levels.

The mean difference in MMSE score between the first and third tertiles of serum DDE was -1.70 (95% CI minus 0.11-minus 3.29) among those with the APOE4 genotype, versus -0.53 (95% CI minus 0.43-minus 0.62) for those with APOE2/3 genotypes (P=0.04 for interaction).

A weakness in the study identified by the editorialists as well as Potter was that, when the two study cohorts were analyzed separately, the association of DDE with Alzheimer's disease risk was not statistically significant in either. It became significant only when the data were pooled.

Consequently, Potter said, the results should be considered preliminary. He noted as well that noncausal explanations for the association can't be ruled out.

For example, he said, individuals with Alzheimer's disease may simply be more rapid metabolizers of DDT, such that their DDE levels are higher even though their exposure to DDT is not.

DeKosky and Gandy argued that more resources should be directed to uncovering environmental factors that promote Alzheimer's disease, because it appears "less likely" that undiscovered genetic factors will have "new and powerful effects" on the risk.

"The time has arrived to direct resources toward the formation of collaborative teams of epidemiologists, toxicologists, geneticists, and dementia researchers," they wrote, with collaborations among the various NIH institutes and other public and private partners.

The study was funded by the NIH.

Study authors declared they had no relevant financial interests.

DeKosky reported relationships with AstraZeneca, Merck, Elan/Wyeth, Novartis, Lilly, Janssen, Helicon, Genzyme, Baxter, and Pfizer. Gandy reported relationships with Baxter, Polyphenolics, Amicus, Janssen, DiaGenic, and Cerora.