Brain's Ability to Clear Amyloid Declines With Age

As people age, the brain takes longer to clear amyloid-β, which may explain why risk for the disease increases with age, researchers say.

"This study identifies a link between the single greatest risk factor for Alzheimer's, a person's age, and the amyloid-β protein that is postulated to cause Alzheimer's," Randall J. Bateman, MD, Charles F. and Joanne Knight Distinguished Professor of Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, told Medscape Medical News.

"With this mechanistic link that amyloid-β half-life slows with increasing age, it may now be possible to predict a person's risk of amyloidosis and Alzheimer's and this will be tested in future studies," Dr Bateman said.

The study was published online July 20 in Annals of Neurology.

SILK Technology

The researchers assessed the relationship between age, amyloidosis, and amyloid-β kinetics in the central nervous system (CNS) in 100 men and women aged 60 to 87 years with sporadic AD, including 56 with clinical signs of AD, such as memory problems, and 62 with amyloid plaques on positron emission tomography. The study also included 12 younger amyloid-negative controls (mean age, 48 years).

The researchers used a technology developed by Dr Bateman and coauthor David Holtzman, MD, chief of the Department of Neurology at Washington University, known as stable isotope labeling kinetics (SILK), which allows for monitoring the body's production and clearance of amyloid-β and other proteins.

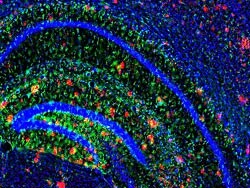

Amyloid plaques (in red). Courtesy of John Cirrito

|

They observed a "highly significant" correlation between increasing age and slowed amyloid-β turnover. The "remarkable" 2.5-fold longer half-life (from 3.8 hours at age 30 to 9.4 hours at age 80) over 4 decades "may account for the increasing liability of amyloidosis associated with aging," they report in their article. As amyloid-β clearance from the CNS slows, the protein may be more liable to aggregation or modification; amyloidosis then increases the risk for cognitive decline and AD, they explain.

The researchers also observed "clear and significant" alterations in amyloid-&beta-42 kinetics in the presence of amyloid deposition. Reduced clearance rates of amyloid-β-42 were associated with clinical symptoms of AD, they report.

The researchers say the mechanism for age-related slowing of amyloid-β turnover is unclear but may be related to structural changes in clearance, decreases in cellular or proteolytic degradation, or decreases in cerebrospinal fluid or blood-brain barrier transport.

"Through additional studies like this, we're hoping to identify which of the first three channels for amyloid beta disposal are slowing down as the brain ages," Dr Bateman said in a news release. "That may help us in our efforts to develop new treatments."

Commenting on the results for Medscape Medical News, Cyrus Raji, MD, PhD, from the University of California, Los Angeles, said this study shows that "as we all grow older, the ability to clear toxic levels of amyloid from the brain goes down, explaining in part the increased risk for Alzheimer's with age."

"The single most critical finding of the paper to me is that impaired clearance of amyloid occurs over time in persons who are showing no signs of memory loss," Dr Raji said. "This is a key observation because any therapeutic or preventive approaches we apply can be optimally effective in persons at risk for the disease but who may not yet show memory loss."

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Adler Foundation, and gifts from Edwin and Barbara Shifrin and Jeff Roschman. Three authors report personal fees for consulting outside the submitted work from C2N Diagnostics.

Ann Neurol. Published online July 20, 2015. Abstract

No comments:

Post a Comment