Topic Alert

Receive an email from Medscape whenever new articles on this topic are available.

Drug & Reference Information

MILAN, Italy — The European Society of Hypertension(ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published new guidelines today for the management of hypertension, simplifying treatment decisions for physicians with the recommendation that all patients be treated to <140 blood="" hg="" mm="" pressure="" style="font-size: 0.85em; line-height: 0;" sup="" systolic="">[1]

The new guidelines do make exceptions for special populations, such as those with diabetes and the elderly. For those with diabetes, the ESH/ESC writing committee recommend that physicians treat patients to <85 blood="" diastolic="" hg="" mm="" pressure.="" span="">

In patients younger than 80 years old, the systolic blood-pressure target should be 140 to 150 mm Hg, but physicians can go lower than 140 mm Hg if the patient is fit and healthy. The same advice applies to octogenarians, although physicians should also factor in the patient's mental capacity in addition to physical heath if targeting to less than 140 mm Hg.

On the whole, Dr Giuseppe Mancia (University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy), cochair of the ESH/ESC writing committee, said there is a shift toward "greater conservatism" with regard to drug treatment in the new guidelines. That said, the guidelines explicitly state physicians make decisions on treatment strategies based on the patient's overall level of cardiovascular risk.

Mancia said the guidelines are not prescriptive, or orders, but rather suggestions for practicing physicians. While there are some aspects of care that remain the domain of expert opinion, he said there is "no question that blood pressures exceeding 140/90 mm Hg increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke," and these are both associated with a massive worldwide socioeconomic cost. Mancia added that 60% of patients remain disabled at one year following a stroke.

ESH/ESC Beats JNC-8 Out of the Gate

Interestingly, the ESH/ESC "Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension," as they are formally called, are published ahead of the much-publicized Joint National Committee (JNC) on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure guidelines (JNC-8). JNC-7 was last published 10 years ago this spring, and US physicians are eagerly awaiting the newest iteration, which has been tagged "JNC-Late." As previously reported byheartwire , many believe the US guidelines will be published sometime this year.

|

Lifestyle Changes for Treatment

Presented at the European Society of Hypertension 2013 Scientific Sessions in Milan, Italy, the new ESC/ESH guidelines are an update to those last published in 2007. According to ESC president Dr Joseph Redon (University of Valencia, Spain), the joint guidelines are designed to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with hypertension. Worldwide, 1.5 billion people currently have high blood pressure, according to the World Health Organization.

Dr Robert Fagard (Leuven University, Belgium), the other chair of the ESH/ESC writing committee, reiterated that treatment decisions for patients should be dictated by their overall level of risk. Such a holistic approach would include an assessment of other cardiovascular risk factors, asymptomatic organ damage, the presence or absence of diabetes, overt cardiovascular disease, or chronic kidney disease.

Like the 2007 guidelines, patients can be stratified into four categories: high-normal blood pressure (130-139 systolic or 85-89 mm Hg diastolic), grade 1 hypertension (140-159 systolic or 90-99 diastolic mm Hg), grade 2 hypertension (160-179 systolic or 100-109 mm Hg diastolic), or grade 3 hypertension (>180 systolic or >110 mm Hg diastolic). The presence or absence of other cardiovascular risk factors or organ damage/disease should be then factored into treatment decisions for the management of blood pressure (a full risk-assessment algorithm is included in the guidelines).

Fagard said the new guidelines also make a host of lifestyle recommendations for lowering blood pressure. He said they are recommending salt intake of approximately 5 to 6 g per day, in contrast with a typical intake of 9 to 12 g per day. A reduction to 5 g per day can decrease systolic blood pressure about 1 to 2 mm Hg in normotensive individuals and 4 to 5 mm Hg in hypertensive patients, he said.

While the optimal body-mass index (BMI) is not known, the guidelines recommend getting BMIs down to 25 kg/m2 and reducing waist circumferences to <102 4="" 5="" 7="" about="" aerobic="" and="" as="" blood="" by="" can="" cm="" endurance="" fagard.="" hg="" hypertensive="" in="" kg="" losing="" men="" mm="" much="" notes="" patients="" pressure="" reduce="" span="" systolic="" training="" while="" women.="">

To heartwire , Fagard said that physicians can typically give low/moderate-risk individuals a few months with lifestyle changes to determine whether they're having an impact on blood pressure. They should be more aggressive with higher-risk patients, however, noting that drug therapy is started typically within a few weeks if diet and exercise are ineffective.

Role for ABPM

One aspect that is new to the 2013 guidelines is an emphasis on ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring (ABPM). The major advantage of out-of-office blood-pressure monitoring is that it provides a large number of measurements outside the medical environment. In addition, out-of-office blood-pressure measurements are more closely correlated to end-organ damage and cardiovascular events than office blood-pressure measurements. While office blood pressure is still the gold standard for the diagnosis of hypertension, Fagard said the 2013 guidelines are the first to consider out-of-office blood-pressure measurements in the risk-stratification model.

"We must say that the two methods are not exactly the same," said Fagard. "They provide different information and should be regarded as complementary."

In addition to emphasizing the role for ABPM, Mancia said the guidelines reconfirm the importance of combination therapy, mainly because "there is no question that many patients need more than one drug for their blood pressure to be controlled." In patients at high risk for cardiovascular events or those with a markedly high baseline blood pressure, Mancia said that physicians can consider starting patients with combination therapy rather than a single drug. In those at low or moderate risk for cardiovascular events or with mildly elevated blood pressure, a single starting agent is preferred.

"This is common sense," said Mancia. "If you have a high-risk individual, you can't play around with one drug after another, trying to control blood pressure, because an event can be just around the corner. We need to control blood pressure within a reasonable time, and combination therapy, of course, allows this more frequently than a single drug treatment."

To the media, Mancia said the evidence from individual studies and meta-analyses indicates that the main beneficial aspect of treatment is blood-pressure lowering per se, rather than how it is achieved. The main classes of drugs--diuretics, beta-blockers, calcium-channel antagonists, ACE inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)--all reduce blood pressure and have similar effects in terms of reducing cardiovascular events.

"What this means is that five different classes of drugs can be suggested for any situation and the maintenance of hypertension treatment," said Mancia.

Even beta-blockers, which are "treated badly" by several other non-European countries, have a role, he added. Some of the "preferred" combinations include thiazide diuretics with ARBs, calcium-channel antagonists, or ACE inhibitors; or calcium-channel antagonists with ARBs or ACE inhibitors, noted Fagard.

The ESH/ESC guidelines do recommend against dual renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockade--ARBs, ACE inhibitors, and direct renin inhibitors--in clinical practice because of concerns of hyperkalemia, low blood pressure, and kidney failure. The EMA recently started its own review of the safety of dual RAS blockade on the basis of a 2013 BMJ meta-analysis showing an increased risk when ARBs and ACE inhibitors were used together.

As for the cancer signal that has recently been attached to ARBs, the committee unequivocally stated that such a risk has been disproven. The US Food and Drug Administration and a review by theEuropean Medicines Agency have both concluded that no such a cancer risk exists, said the panelists during the press conference.

Resistant Hypertension

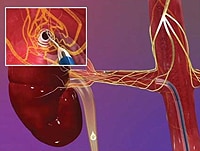

One interesting aspect of the new guidelines is that renal denervation, a quickly growing and frequently hyped treatment within the cardiology community, is simply labeled as a "promising" therapy in the treatment of resistant hypertension.

The committee said that renal denervation is in need of additional data from long-term comparison trials to establish safety and efficacy against the best possible drug regimens. Moreover, there is also a need to determine whether the reductions in blood pressure achieved with renal denervation translate into reductions in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, something that has never been proven.

Mancia reports speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy payments, and advisory board fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Servier, Sanofi, Menarini, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Recordati, Daiichi Sankyo, and Medtronic. Redon reports speaker fees, honoraria, consultancy payments, and advisory board fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Menarini, Merck, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Daiichi-Sankyo. Fagard reports receiving honorarium from Servier. Disclosures for other members of the writing committee are available here.

No comments:

Post a Comment