How to Quarantine … in 1918

From atomizer crazes to stranded actor troupes to school by phone, daily life during the flu pandemic was a trip.

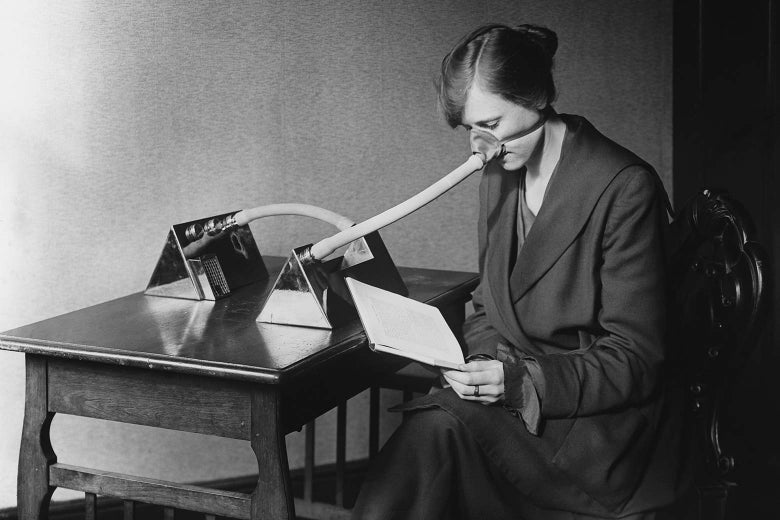

A woman wears a flu mask during the 1918 pandemic.

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images

Slate is making its coronavirus coverage free for all readers. Subscribe to support our journalism. Start your free trial.

In October 1918, during the peak of the flu in the United States, an epidemic of boredom tore through a group of 50 vaudeville actors marooned in Salt Lake City. “We’ve done everything from sightseeing to window shopping, and we’ve done it over and over again,” one actor told the Salt Lake Herald-Republican, adding that they’d played blackjack “until the sight of a card fairly nauseated us.”

The actors had no particular connection to Salt Lake. They’d been in the middle of a tour, performing musicals two to three times per day. But by October, policy failures in cities like Philadelphia were translating into surging death counts, and much of the U.S. was jarred into cracking down on public gatherings to stop the flu. In Salt Lake City, officials closed all theaters. Meanwhile, trains across the country were severely curtailing service. With no work and no place to go, the actors became a drag on resources. They started singing and dancing in the streets. Some tried selling Liberty Loans—government war bonds to support the American World War I effort—but the city lockdown often stymied those efforts. As the crisis continued, the Salt Lake Herald-Republican begged, “Will someone oblige some fifty actors and actresses now in Salt Lake by introducing into their midst a new wrinkle or so in the general art of killing time?”

The 1918 flu is not a perfect comparison point for COVID-19. For one thing, flus are different from coronaviruses. For another, disease knowledge and infrastructure in the teens was far behind where it is now. Scientists in 1918 had never actually laid eyes on a virus up close. That’s not to mention the existence of World War I in 1918, or the fact that while COVID-19 has generally been shown to be more deadly in older adults, the people most vulnerable to the 1918 flu were ages 20 to 40. But the 1918 flu is also the last time large swaths of Americans found themselves quarantined because of a pandemic, and an analysis of contemporaneous newspaper accounts reveals that #QuarantineLife in 1918 was just as mundane and arbitrary—and occasionally surreal—as it is now.

Lockdown in 1918 did, of course, have different rules than lockdown today. Even in those cities that took the most decisive action—St. Louis was warning residents to avoid crowds before the virus had even reached the city—some basic tenets differed. For instance: To the chagrin of those suffering Salt Lake City actors, not all cities closed their theaters. In Hamilton, Montana, local policy allowed movie theaters to stay in business as long as customers left a seat between each other.

Bookstores also sometimes remained open, and they reported massive spikes in customers. According to the Wichita Daily Eagle, “Wichita book stores are enjoying excellent trade in magazines.” As soon as a new issue of a popular magazine published, customers raced to snatch it off the stands. One good case study is Decatur, Illinois. During the lockdown, the city of Decatur was reeling; when “even parties of the most informal sort were called off,” Illinoisans “were thrown upon their own resources for amusement.” Public dinners were “out of the question” for the simple reason that “it’s hard to eat wearing [a] ‘flu’ mask.” So residents turned to magazine stands. One local dealer reported to the Decatur Herald & Review that he was constantly sold out, leading the newspaper to conclude that “if the quarantine last[s] much longer, the magazine and fireside habit will have such a hold that it will be hard to break.”

That gave advertisers a venue to hawk their products despite the sudden halt of most social life. In early November, an Iowa candy store ran a photo of a woman in heels and a cloche hat and asked, “All dressed up but no place to go?” The store directed customers instead to “just stay home” (sound familiar?) and “pass the time away with a nice box of candy.” Other companies rolled out “Pass Time Puzzles” to keep kids occupied during the pandemic. (So far, with COVID-19, the opposite has proven true: The advertising market has bottomed out, and magazines and publishers are facing layoffs and pay cuts in record numbers.)

In 1918, many people refused to leave their houses without atomizers—water vapor sprays that, it was believed, helped prevent disease by keeping nasal and throat passages clear. Trains saw their lowest ridership numbers in U.S. history, according to some newspaper reports, and passengers who did venture on board clutched atomizers for dear life. The Asheville Citizen-Times wrote about one man who sprayed every passenger in his car—including the porter—with an atomizer in an effort to inoculate them from disease. “Introducing himself, he said he wanted to tender the use of his atomizer to each of his new acquaintances and practically all of them enjoyed a good spray,” said the Citizen-Times, adding that the man carried his atomizer “as though it had been an automatic.” On these near-empty train rides, women also pretended to sneeze and act sick to deflect unwanted male attention.

Meanwhile, rumors were running rampant, often amplified by the tensions of World War I. One claim, pushed by pro-Germany propagandists, insisted that U.S. physicians were giving soldiers medicine that would simply kill them rather than speed up their recovery. In Louisville, Kentucky, the lie made such a sensation that the district attorney announced on Oct. 18 that he would prosecute anyone caught spreading it. Other lies were totally legal: The beef extract Bovril was marketing itself in U.S. newspapers as a potential cure for the flu, noting that “its bodybuilding powers were … needed to fight the influenza epidemic.”

But like today, one defining fact of quarantine life was the patchwork of local laws under which people lived. In Chicago, if you coughed or sneezed, patrolling police officers would ensure you were holding a handkerchief. The city also banned smoking on public transport for the first time, reasoning that smokers would be more likely to cough and accidentally spread disease. In Seattle, new laws enacted harsh fines for people caught spitting on the street. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, considered rules that would require manufacturing workers to clock out in staggered intervals in hopes of neutralizing rush hour. San Francisco continued legal proceedings, but court was held in the open air. Localities like Washington state and Davenport, Iowa, mandated flu masks in all public places, from theaters to churches. In Iowa, streetcars were limited to 75 passengers at a time, and conductors who allowed more people risked arrest.

Yet some of the strangest laws centered on restaurants, as Jan Whitaker recounted in her blog Restaurant-ing Through History. In very few cities did local health officials fully shutter restaurants. Some municipalities did limit open hours, but in general, health officials considered restaurants an essential service. Many people lacked access to iceboxes, making enormous grocery stockpiles near impossible. Especially for working-class people living in crowded tenements without kitchens, restaurants were often the only way to find a meal. Eating home-cooked meals was a measure of wealth.

That is not to say that regulations skipped over the restaurant business entirely. Many places required that restaurants scald all their dishes in hot water so that they’d be sterilized, according to Whitaker. Other cities and states asked that cooks and servers wear masks and that tables be spaced at least 20 feet apart. But, to discourage people from gathering in groups, some municipalities passed a series of laws limiting the degree to which everything from alcohol to ice cream could be served.

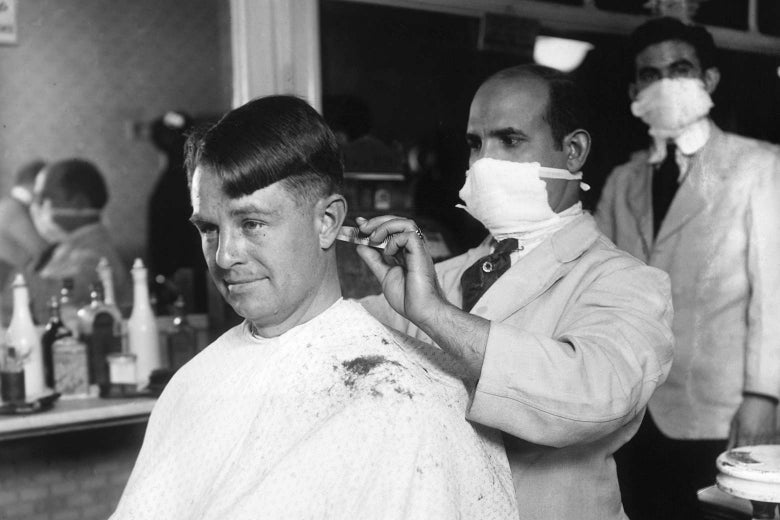

Precautions taken during the influenza epidemic.

Bettmann/Getty Images

In Harrisburg, health authorities took aggressive measures to protect the city from the flu—canceling all public meetings, requiring private funerals, limiting the number of hospital visitors, and shutting down soda fountains. But while restaurants were permitted to operate, they could not serve single meals of ice cream or pie. Customers could order desserts if they also ate a full meal at the restaurant, but stand-alone orders of ice cream were banned, and restaurants that failed to comply risked prosecution. The bizarre ice cream order caused a small stir in the city, but as the Harrisburg Evening News explained, “the whole idea is to prevent persons congregating.” Apparently, nothing facilitated socializing like ice cream and pie.

Maybe no fact of quarantine in 1918 resonates as much today as the awkward position it left the education system in. In 1918, schools across the country closed for the flu. Like colleges today, some made the promise that classes would continue remotely—except instead of Zoom, teachers had to rely on telephones.

The problem was students weren’t having it. In Columbus, Ohio, after authorities closed the schools, “instructions were given that pupil and teacher so situate themselves that they could hold telephone consultations regarding lessons.” But according to one teacher, “I have been sitting at the end of a telephone ever since the schools closed, and I have not heard from a single pupil for a month.”

No comments:

Post a Comment