The Greatest Unknown Intellectual of the 19th Century

Emil du Bois-Reymond proclaimed the mystery of consciousness, championed the theory of natural selection and revolutionized the study of the nervous system. Today he is all but forgotten

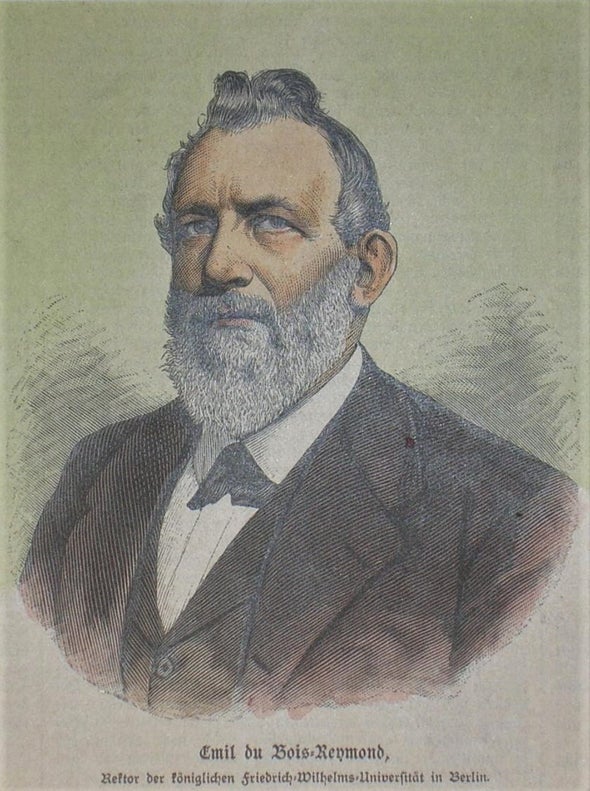

Unlike Charles Darwin and Claude Bernard, who endure as heroes in England and France, Emil du Bois-Reymond is generally forgotten in Germany — no streets bear his name, no stamps portray his image, no celebrations are held in his honor, and no collections of his essays remain in print. Most Germans have never heard of him, and if they have, they generally assume that he was Swiss.

But it wasn’t always this way. Du Bois-Reymond was once lauded as “the foremost naturalist of Europe,” “the last of the encyclopedists,” and “one of the greatest scientists Germany ever produced.” Contemporaries celebrated him for his research in neuroscience and his addresses on science and culture; in fact, the poet Jules Laforgue reported seeing his picture hanging for sale in German shop windows alongside those of the Prussian royal family.

Those familiar with du Bois-Reymond generally recall his advocacy of understanding biology in terms of chemistry and physics, but during his lifetime he earned recognition for a host of other achievements. He pioneered the use of instruments in neuroscience, discovered the electrical transmission of nerve signals, linked structure to function in neural tissue, and posited the improvement of neural connections with use.

No comments:

Post a Comment